Controlling nature by bulldozing dirt and pouring concrete has long been the guiding vision of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. For 250 years that ethos inspired both awe and disgust. “In my science training, the Army Corps destroyed everything. They’re the enemy,” says geomorphologist Julie Beagle, who spent much of her early career working to repair ecosystems damaged by “gray” infrastructure such as dams and levees built by the Corps. “My first boss had a sign on her desk that said, ‘Kill the Corps.’” To such critics, damaging nature was the Corps’s core competence.

So plenty of people were skeptical in 2010 when the Corps rolled out an Engineering with Nature (EWN) initiative, saying it now aspired to work with nature rather than dominate it—a dramatic change in culture and practice. Engineers and scientists are moving constrictive levees farther from riverbanks and reconnecting rivers with floodplains. They are reusing sediment dredged from shipping channels to strengthen disintegrating tidal marshes. They are partially acquiescing to rivers’ chosen paths while retaining navigation channels.

The initiative is relatively small; there are seven EWN programs sprinkled across the Corps’s 43 districts (five of which are international). But the changes convinced Beagle four years ago to leave her job at the San Francisco Estuary Institute and become chief of environmental planning for the Corps’s San Francisco district. She is now one of four “practice leads” who demonstrate and teach EWN across the Corps’s 37,000 employees. One example of her pioneering work is a big project in central California’s Pájaro River basin designed to protect communities from flooding while recharging groundwater to aid farmers and restoring habitat for threatened fish.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Beagle’s career move was risky, given the Corps’s inertia. Its long insistence that it could and should reshape nature for economic benefit has dominated U.S. civil works culture and has been exported globally through Corps projects in more than 130 countries, a practice some call “hydrocolonialism.”

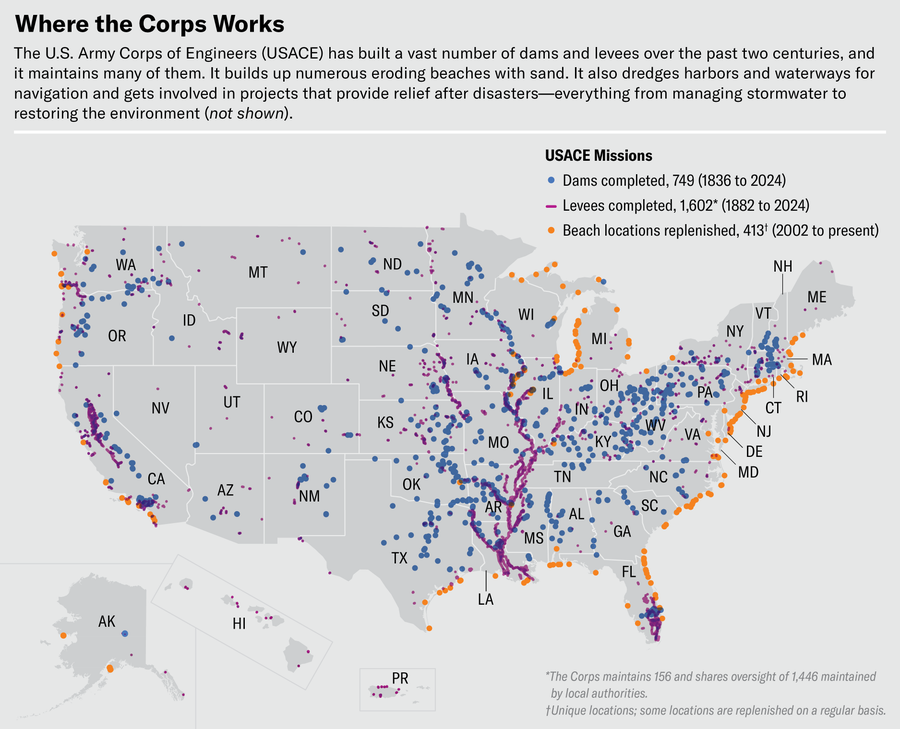

Beagle says many people from her adviser’s generation “really rolled over” when she and several other mid-career scientists she knew went to the Corps. But she saw the move as an opportunity to be “a cultural changemaker” in an agency that has remade vast landscapes and waterways. With a $7.2-billion budget for civil works in fiscal year 2025, the agency’s employees oversee 24,000 miles of levees; 926 harbors that they keep dredged for shipping; 749 dams; 350 miles of beaches and dunes; numerous navigation channels and locks; and seawalls and bulkheads along hundreds of miles of coast. How the Corps thinks and what it does shape our world.

Levees are built to control nature, but nature often wins, as it did during the Pájaro River flood.

The consequences of its decisions can be deadly. The most horrific failure in recent memory occurred during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. More than 1,400 people in New Orleans and the Gulf region died when levees and floodwalls gave way; 80 percent of New Orleans lay underwater, some areas for 43 days. The Gulf’s famous marshes help to protect human communities from storm surges, but more than a century of levees and dams on the Mississippi River had deprived the marshes of 70 percent of the sediment they need to stand up to a relentless sea. More than 2,000 square miles have eroded away since the 1930s. Shipping canals have sliced and diced freshwater marshes, providing pathways for salt water to infiltrate and kill vegetation and for storm surges to rear up and overtake near-shore communities. Katrina bowled straight up a wide navigation channel called the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet that the Corps had cut through protective marshes.

The Corps’s subsequent shift toward nature-based solutions—working with or mimicking natural systems—is part of an increasingly mainstream global movement. The 160,000-member American Society of Civil Engineers issued a policy statement last summer supporting the practice. People are increasingly recognizing the need for nature-based solutions as climate change is making floods and droughts more severe, and changes in land use—urban sprawl, industrial agriculture and forestry, levees and dams—have dramatically altered the water cycle and eroded healthy ecosystems that for centuries acted as buffers to destruction.

Nature-based solutions mean restoring the health of degraded ecosystems so they can provide clean water, absorb floods, store carbon, grow food and support life. Eileen Shader, senior director of floodplain restoration at American Rivers, a nonprofit that advocates for healthy waterways, says that in some cases, “you’re solving the problem by unbuilding.” Still, the Corps’s concept of nature-based solutions tilts more toward engineering and concrete. As Jeff King, national lead of the EWN program, puts it, projects fall somewhere on “a continuum of green-gray.”

“You could call the 20th century the century of reinforced concrete. My hope is the 21st century is the century of nature.” —Todd Bridges, University of Georgia

The approach could rapidly become more widespread thanks to a Corps rule that went into effect in January 2025 that requires the agency to consider nature-based options on par with gray infrastructure options whenever feasible. The rule also expands the traditional cost-benefit analysis to factor in environmental and social gains of projects, even if it’s impossible to assign a dollar figure. It is “the most significant policy-change update for the Corps in a generation, without a doubt,” says biologist Todd Bridges, who in 2010 created the EWN program out of the Corps’s research division, where he worked for 30 years.

Within weeks after President Donald Trump took office this year, his new administration began purging federal government websites of language that seemed progressive, freezing funds for scientific research, and dismantling departments that support human rights, science and the environment. It’s reasonable to ask whether EWN—a progressive shift in a conservative agency—would be a target. The Project 2025 manifesto guiding many administration actions mentions the Corps only once, in passing, but that doesn’t mean the agency will go untouched. At the end of January, in an unusual act, Trump ordered the Corps to release water from two federal reservoirs in California, with a stated goal of letting it flow about 200 miles south to help fire-ravaged Los Angeles. The Corps released 2.2 billion gallons, but the water did not come close to reaching the city. Local water managers scrambled to prevent flooding of nearby towns, while farmers were dismayed to see water they will need in the summer flushed away.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is the engineering wing of the U.S. Army. Despite its military basis, its workforce today is 98 percent civilian. Its civil works division is tasked with navigation, reduction of flood and storm damage, and environmental restoration. Local groups lobby Congress for work in their areas, and Congress authorizes projects and partial funding. Congressional authorizations have historically proscribed a single objective, such as flood-risk reduction, a narrow focus at odds with the systems-oriented thinking required for nature-based solutions.

The Corps’s urge to try to control nature was solidified in the mid-19th century, when dueling congressional reports outlined how to reduce Mississippi River flooding and ensure navigation. One advocated for a hybrid engineering-nature approach—using not only levees but also outlets to release high river flows, as well as wetlands to absorb rain. It lost out to another vision authored by a Corps engineer who argued for a levees-only approach. The belief that strong walls can best protect communities has dominated the engineering psyche ever since. But the unintended consequences can be extreme.

Florida’s Kissimmee River was an early, expensive lesson. In response to prolonged flooding in 1947, the Corps wanted to rush away high river water instead of letting the river overflow onto its floodplains and wetlands. To create a straighter channel with faster water flow, it spent nine years, from 1962 to 1971, cutting out the river’s natural meanders that slow water, shortening the waterway from 103 miles to just 56. The work dried out thousands of acres of wetlands and floodplains, harmed wildlife and increased the flow of pollution into Lake Okeechobee. Damage was immediate and so extensive that Congress authorized the Corps to put back the curves. “A hallmark of 20th-century engineering is that people simplified the natural in order to get what we want,” says Bridges, now a professor of practice in resilient and sustainable systems at the University of Georgia’s College of Engineering. Then he corrects himself: “What we think we want.”

Ripley Cleghorn; Sources: National Inventory of Dams; National Levee Database; USACE’s Dredging Information System (data)

Simplifying the natural order can even worsen the problem engineers are trying to solve. Today 3,500 miles of levees line the Mississippi River. Each levee constricts space for water, raising the surface level higher, speeding up its flow, and worsening flooding for communities that lack a levee or are near one that breaks. Yet the Corps evaluates each new levee on its own immediate merits, not in conjunction with those on the rest of the river. As geomorphologist Nicholas Pinter of the University of California, Davis, has written, even the Corps has acknowledged that the result is “‘death by a thousand blows,’ through the incremental loss of floodplain land to development.”

Another unintended consequence is that levees encourage people to move into harm’s way. The Great Flood of 1993 left areas around the Missouri and upper Mississippi Rivers above flood stage for up to 195 days. The Corps worked with a St. Louis levee district to build a 500-year levee—an awkward term meaning the levee would limit the risk of flood in any given year to 0.2 percent (statistically, there is a one-in-500 chance of a flood happening any year). The levee made people feel safe enough to build, in the first decade alone, 28,000 new homes and more than 13 square miles of commercial and industrial development and roadways on land that had been underwater. But it’s a false sense of security, revealed by a dark industry joke that there are two kinds of levees: ones that have failed and ones that will fail. “People think, ‘Why do I flood?’” says Jo-Ellen Darcy, board chair of American Rivers. “Well, you’re living in a floodplain. They’re not named that for no reason.” Indeed, floodplains are a classic nature-based solution. Their job, Darcy says, is “to absorb floods, and they can’t do that if people are living there with concrete structures and malls.”

Katrina was a turning point in the Corps’s approach, says Jane Smith, who was a senior research scientist there for 42 years and is now a professor of coastal hydrodynamics at the University of Florida. When Smith and her colleagues ran models after the storm, she says, “we started to see how incredibly important the wetlands were in terms of protection from hurricane storm surge and waves.” Before that, “we didn’t really think of the natural features that provide protection as being part of our projects,” she adds. But Bridges recalls that many Corps employees outside the research division weren’t ready to hear it. He says an engineer told him, “We don’t need any of that tree-hugger science.”

Before joining American Rivers, Darcy led the Corps’s civil works as an assistant secretary of the U.S. Army from 2009 to 2017. During her tenure she emphasized an important tweak in language used by the Corps. “It wasn’t ‘flood control,’” she explains. “Nobody can control a flood.” She used “flood-risk reduction,” which acknowledges that reality—and sends a message within the Corps and to the public about the limits of what’s possible.

Shader, at American Rivers, works with the Corps nationally and says the agency’s current openness to what she considers effective nature-based solutions varies geographically. “San Francisco is absolutely the lead,” she says. “They have a dedicated staff that is working to create interdisciplinary teams and integrate these concepts into every project.” That’s partly thanks to Beagle, who showed people across the Corps how to take a big standard project and insert nature-based solutions.

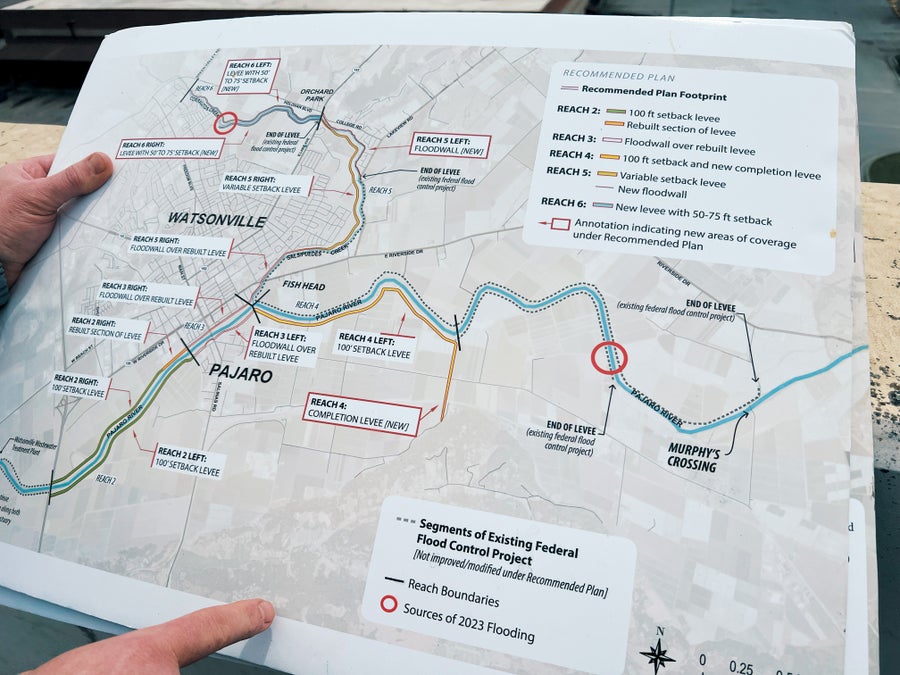

In March 2023 an atmospheric river storm struck central California, bursting three levees on the Pájaro River and flooding the eponymous town, which is populated by farmworkers and surrounded by fields of berries and greens. The disaster wasn’t a surprise; the four- to 12-foot-high levees lining the river and its two tributaries, Corralitos Creek and Salsipuedes Creek, dated to 1949 and promised just eight-year flood protection—which equates to a 12.5 percent chance of flooding in any year. In 1966 Congress authorized the Corps to build taller, wider levees, but partly because the economics of protecting the low-income community didn’t seem to work out, the project never moved forward.

The Corps later realized that adequate protection required giving the waterways more room. It wanted to move some of the long earthen levees that run for 13 miles along both sides of the waterways farther back from the banks. These “setback levees” would create extra space between the levees to hold more water during high flows, reducing overflow flooding.

Julie Beagle is leading an innovative Army Corps project that shows how to work with nature.

That solution required local people to give up some of their land, and residents resisted for decades. But as the toll of repeated floods mounted, they finally gave in, says Mark Strudley, executive director of the Pájaro Regional Flood Management Agency, a local partner to the Corps. Strudley says farmers in the area realized they were having a hard time cultivating that soggy land, anyway. In October 2024 the Corps broke ground on the multiyear project, known internally as “100 for 100.” It bought up to 100 feet of landowners’ properties along the waterways, offering in return 100-year flood protection: a 1 percent chance of flooding in any year.

But Beagle saw that this standard project could be tweaked to simultaneously solve another local problem: a declining groundwater table caused by farmers’ overpumping. When a wild river runs high, water overflows the banks, spreads across the floodplain and slows. It has time to sink underground to supply aquifers, deposit soil nutrients and fine dirt that continually reshape the river, and create habitat that supports fish. But in the decades that the river and its tributaries had been cut off from their floodplains, water squeezing through the levee-narrowed river channel had run faster. Speed gave it power to cut down into the earth, leaving the creeks about 10 to 25 feet lower than the surrounding farmland. If the Corps just set the levees back, Beagle knew, the river would reach the riverbanks only when it ran really, really high. Most of the time water would still be stuck down in the channel, speeding away. It wouldn’t have a chance to replenish groundwater, redistribute soil or help fish.

Beagle and Strudley convinced the Corps to turn the plan into an EWN project by pointing out that the change would in fact save money. To build the new, wider levees, the Corps would have had to truck in dirt, which is expensive. Instead it will excavate much of the dirt from the former farmland that will now be inside the setback levees. It will also dig in a way to re-create some of the river’s natural functions, fashioning side channels and earthen steps from the new levees down to the creek. When the river runs high, the channels and steps will slow water, giving it time to sink underground inside the setback levees. This action will refill dwindling groundwater reservoirs and increase flood protection by ensuring some water gets absorbed by the ground and moving the rest of it downstream over a longer period.

The design will also allow sediment swishing around within the wider riverbed to create an accessible floodplain again. The river will reshape what the engineers build, and that’s okay, Strudley says. “‘Correcting’ is fighting physics,” he says, “which in general doesn’t end well and wastes a lot of money.”

The higher water table will allow farmers to pump water more easily and will feed the creek in the dry season. Slow water inside the levees will allow algae and plankton to grow, feeding fish such as the South-Central California Coast steelhead, a threatened species, and providing refuges where they can rest during their mating migration upstream. The more natural waterway will attract other wildlife, perhaps creating recreation spots for residents and even attracting ecotourists.

Although multiple benefits are beyond the singularly focused congressional authorizations, local and state partners want them. Strudley worked with California’s Department of Water Resources, which ponied up the local funding because it is motivated to reverse dropping water tables. “Recognition of those benefits is why the state invested,” Strudley says. “Multibenefit is how you get things done these days. The Army Corps is catching up to that.”

Reconfiguring levees along the Pájaro River and its tributaries to slow down rushing storm water will protect people nearby, resupply underground aquifers and restore fish habitat.

Scientists from universities in the area are studying those benefits, measuring how 100 for 100 will affect groundwater recharge, sediment movement and fish populations. Quantifying the benefits is fundamental, says King, the national head of EWN, “because engineers have to feel comfortable understanding how these things are going to perform.”

Many of these concepts are commonplace in restoration circles, Beagle says, but not so familiar to engineers. “Reading the landscape and understanding how nature works is a different set of skills,” she says. The Corps has a manual for how to build a levee, but it does not have one for floodplain reconnection. It will soon, though. Beagle has co-written national guidelines for floodplain reconnection in the same format as Corps instructions for building a levee, with “equations, loadings, shear stresses, things like that,” she says.

Part of Beagle’s role is to educate Corps employees from other districts as they do rotations in the San Francisco district. “It’s really, really satisfying to watch these ideas take off,” she says. She still encounters resistance, however. Some colleagues complain that nature-based solutions are a headache and more expensive because they think these approaches mean adding bells and whistles to an existing project. Yet engineering with nature is often less expensive, Beagle says: “A healthier system maintains itself to a larger degree.”

Each of the Corps’s six other EWN proving grounds has its own Pájaros—projects that showcase new approaches. Monica Chasten, head of EWN in the Philadelphia district, is shoring up disintegrating marshes near the southern tip of New Jersey in a 24-square-mile area known as the Seven Mile Island Innovation Lab. Her specialty, coastal engineering, is fundamentally different from civil engineering. “It’s not like designing a bridge,” she says. “Not everything is exact. It’s almost like an art.”

Hurricane Sandy was a revelation in the region because marshes and dunes did an especially good job of protecting people. Softer than seawalls, they absorb wave energy rather than bouncing it onto neighboring stretches of coast. But sea-level rise and sediment scarcity threaten to destroy half of the region’s marshes by 2100. The scarcity is partly the result of a long-standing Corps practice. When it dredged fine sediment to maintain coastal shipping channels, it dumped the material into inland basins to simplify compliance with regulations aimed at protecting coastal areas from possible pollutants in the sediment. But in 2023 chief of engineers Lt. Gen. Scott A. Spellmon (now retired) realized the Corps was throwing away valuable material and set a goal that by 2030 it would reuse 70 percent of everything it dredged.

Chasten says her district is on track to go beyond that. Some of the fine-grained sediment the Corps dredges from the New Jersey Intracoastal Waterway floats in from the marshes to begin with, so Chasten’s team is pumping clean sediment back into the needy marshes. The impact will be transformative, predicts Lenore Tedesco, executive director of the Wetlands Institute, a New Jersey organization that works on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and is a partner to the Corps. “We’ve built 30 to 50 years of resilience into that marsh,” she says.

Engineering with nature can save money because a functional ecosystem is likely to require less maintenance than fully engineered infrastructure.

A thousand miles away the Corps’s St. Louis district is following nature’s lead to unravel a problem that the agency helped to create there: floodplain occupation. Edward Brauer, a hydraulic engineer and an EWN project lead, has been relinquishing part of a floodplain to the Mississippi River in Dogtooth Bend, a 17,000-acre chunk of Illinois inside a U-shaped turn of the river that borders Missouri.

In the 19th century the area was a rich, shifting blend of wetlands, floodplain lakes, bottomland hardwood forest, cypress and tupelo slough, and cane thickets. “The river did what rivers do and meandered across the landscape,” Brauer says. Levees the Corps installed to create farmland were essentially seeking to stop time. But “it’s a constant battle with the river,” EWN founder Bridges says.

And the river is on a roll. The area has flooded increasingly often—in 1993, 2011, 2016, 2017 and 2019—repeatedly washing out roads, ruining crops, and flooding homes in Olive Branch and Miller City. During major breaches, one third of the Mississippi’s flow gushes overland, taking a shortcut across the U. In 2019 Dogtooth Bend was inundated for nearly nine months.

Letting the river make the cut might be the most nature-based solution. But the Corps also has a mandate to maintain shipping channels. Brauer is trying to negotiate a truce. Residents tired of repeated flooding have accepted buyouts. On those newly available lands, Brauer’s district is restoring natural floodplains and bottomland forests—habitat for at-risk species that also accommodates the river, reducing the frequency and force of its thrusts across the bend. The vegetation slows water and catches sediment that might otherwise move downstream, reinforcing the existing channel instead.

Projects such as Pájaro, Seven Mile and Dogtooth Bend may become more common thanks to key points in the new rule: requirements for equal consideration of nature-based solutions, as well as a broader cost-benefit analysis. The rule, called for in congressional legislation dating back to 2007, was drafted in 2013, but passage was stymied for years by congresspeople who didn’t want the Corps to stop weighting economics over all other things. That dynamic shifted in 2021 when R. D. James, appointed by Trump as the assistant secretary for civil works, became concerned that low-income communities suffering from the massive 2019 Mississippi River floods were being bypassed by the standard cost-benefit analysis. So he wrote a memo outlining the inclusion of social and environmental factors.

Still, the new rule does not correct a fatal flaw in standard cost-benefit analyses. A gray project’s destruction of natural systems’ services—absorbing floods, cleaning pollution, providing water in the dry season, generating food, storing carbon dioxide—is not counted against its benefits. Nor does the Corps deduct for a project’s likelihood of increasing flood risk in neighboring communities that are not protected.

American Rivers provided input for the rule, and Shader says she’s glad it finally passed. But she’s concerned that it doesn’t provide criteria for choosing between nature-based solutions and gray projects, such as accurately tallying the potential losses. “So it really depends on that individual district and the nonfederal sponsors’ interests,” she says.

Trump is likely to choose a new assistant secretary for civil works in his current presidential term. Michael L. Connor, who held that position until October 2024, said then that he’s hopeful the rule will not be overturned. “I don’t think this is a politically controversial rule,” he says. “We were directed to carry this out by the Water Resources Development Act in 2020 that was enacted during President Trump’s term and by a split Congress,” he said. “[It’s] an initiative that has broad support across the spectrum.” Although the new administration was disrupting government in its early days, Darcy says examples of local partners gaining multiple benefits may be politically powerful enough to convince the president and Congress to leave the new rule alone.

Perhaps it is dawning on people throughout Congress and the Corps that “the control of nature”—the title of writer John McPhee’s 1989 book about the Corps—is futile. McPhee wrote then that “the Corps has been conceded the almighty role of God.” Subsequent decades have been a reckoning with the almighty power of nature. Regardless of the rule’s fate, the Corps is part of an ongoing, global shift toward nature-based solutions as people recognize the design savvy of harnessing that power. “The 20th century, you could call it the century of reinforced concrete,” Bridges says. “My hope is the 21st century is the century of nature.”