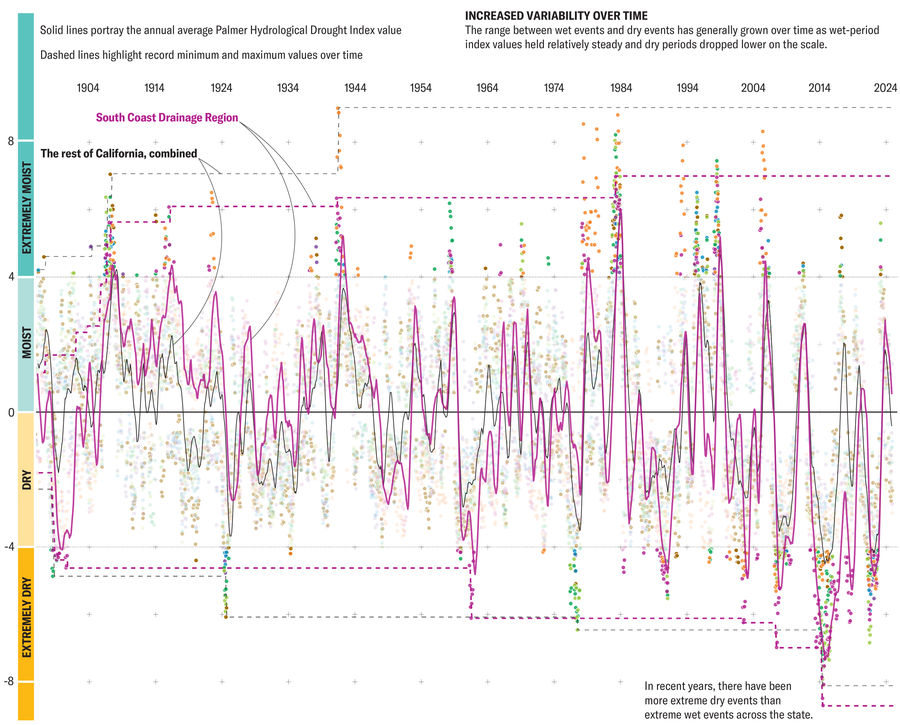

The devastating fires in California early this year came after a particularly unfortunate weather pattern—an exceptionally wet period of about 18 months, followed by an exceptionally dry spell. The wet duration encouraged grass and brush growth, and then the lack of rain dried it all out, priming it to catch on fire and spread quickly.

“It was a classic example of wet-to-dry whiplash,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. And such whiplashes may be getting more common. “With climate change, it’s not just that we’re seeing things get drier and drier. There’s also a trend toward more variability, with wider swings between wet and dry,” Swain says.

The warming climate is leading to what scientists call the “expanding atmospheric sponge” effect. Warmer air can hold more water vapor than cooler air, so the atmosphere is like a kitchen sponge that gets larger. If water is available, the atmosphere will absorb more of it, and when you wring out the sponge, you get more precipitation. But if there is no water to absorb, that thirstier air sucks more moisture out of the landscape, from bodies of water, surfaces and plants, drying everything out.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

PALMER HYDROLOGICAL DROUGHT INDEX

This measurement uses reservoir and groundwater levels, among other factors, to measure drought. Each dot on the chart below represents the drought level for one month in one region of California.

Wesley Grubbs; Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (data)