76 Ways Pregnancy and Giving Birth Change a Person’s Body

Data from 300,000 births reveal how essential biological measurements are altered by carrying and delivering a baby

Women’s bodies undergo vast physiological changes during pregnancy that can last for more than a year after birth.

Catherine Delahaye/Getty Images

Biologists have built up one of the most detailed pictures ever of the changes that occur in women’s bodies before and after pregnancy, by pooling and studying around 44 million physiological measurements from more than 300,000 births.

The gigantic study1, which used the anonymized results of blood, urine and other tests taken before, during and more than a year after pregnancy, reveals the scale of the toll that carrying a baby and childbirth take on the body — from the myriad changes made to support a fetus to the effects of its abrupt departure from the body during birth. The research was published in Science Advances on 26 March.

The study suggests that the postnatal period in the body is much longer than people tend to assume, says Jennifer Hall, who researches reproductive health at University College London. There’s a societal expectation that you bounce back quickly after childbirth, she says. “This is like the biological proof that you don’t.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The results also suggest that it might be possible to identify women at risk of certain common complications of pregnancy — including the blood-pressure condition pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes — before conception. Currently, these conditions are diagnosed during pregnancy.

The power of data

The researchers used anonymized data from medical records supplied by Israel’s largest health-care provider, and spanning the period from 2003 to 2020. To build up a picture of a typical pregnancy, they used test results only from women aged 20–35 years who were not taking medication or experiencing chronic disease.

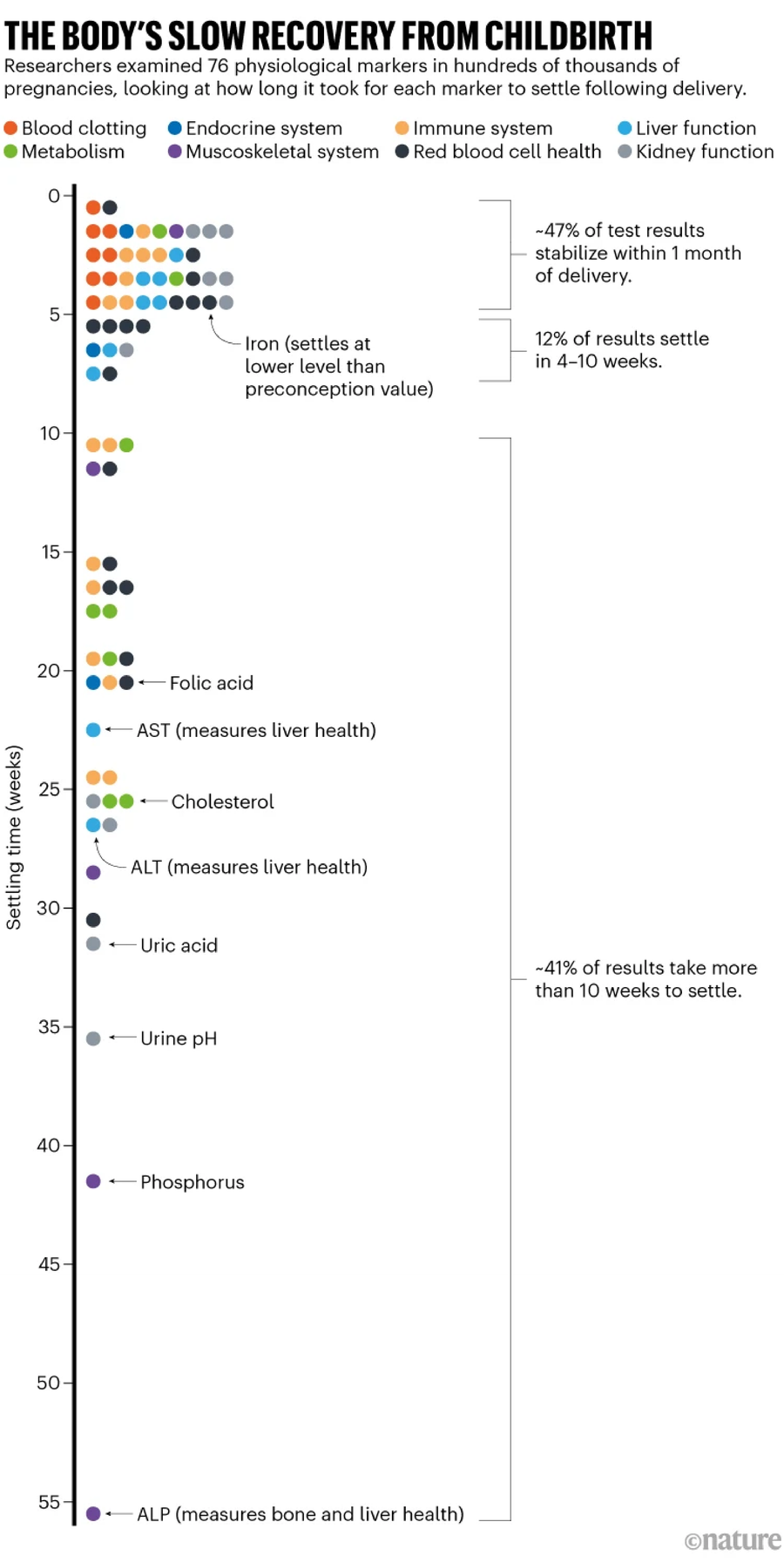

The team gathered results from 76 common tests — including measures of cholesterol, immune cells, red blood cells, inflammation and the health of the liver, kidneys and metabolism — taken up to 4.5 months before conception and up to 18.5 months after childbirth. This allowed them to establish average values for each test for every week in that period.

“It took my breath away to see that that every test has this dynamical profile that is so elaborate, week by week, and has never been seen before,” says Uri Alon, a systems biologist at the Weizmann Institute for Science in Rehovot, Israel, who led the study.

The researchers found that, in the first month after birth, 47% of the 76 indicators stabilized close to their pre-conception values. But 41% of the indicators took longer than 10 weeks to stabilize. These included several measures of liver function and cholesterol that took around six months to settle, and an indicator of bone and liver health, which took a year (see ‘The body’s slow recovery from childbirth’). The remaining 12% took 4–10 weeks to stabilize.

Several measurements — including a marker for inflammation and several indicators of blood health — settled but did not return to their pre-conception levels even after 80 weeks, when the study ended. Whether such long-lasting differences result from pregnancy and birth themselves or from behaviours changing after the arrival of a child is a question for future research, say the scientists.

The researchers classed the indicators into four groups according to their trajectories. Some measures rose during pregnancy, then dropped post-partum; others did the opposite. Others still didn’t just drop or rise to meet pre-conception levels: they over- or undershot their pre-pregnancy values at delivery, before settling at roughly their pre-conception levels. That could be explained by the body ‘overcompensating’ for changes.

Pre-conception changes

The scientists found distinct changes in the body that began even before conception. Some of these — including a reduction in a marker of inflammation and increases in folic acid — were beneficial. The researchers attribute this to the tendency for people to take supplements and live more healthily when trying to conceive.

The researchers also isolated tests from women who developed complications that are currently not diagnosed until pregnancy, including gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia, a condition that results in high blood pressure and can be life-threatening. They found that these women had different profiles for certain markers compared with tests from healthy pregnancies, and in some cases, the differences were most significant before conception.

This finding is exciting, says Hall, because it raises the possibility of being able to identify and help women at risk of these conditions before they conceive.

The findings show the power of anonymized biomedical information to uncover fresh insights, says Alon. His team is now taking a similar approach to studying menopause. “We can ask any statistical question we want,” he says. “It’s like paradise.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on March 26, 2025.