Do you think teeth are boring or gross? From the iron-laden teeth of Komodo dragons to the horns on unicorns of the sea, the animal kingdom is filled with marvelous dental adaptations that will have you thinking again.

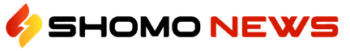

Sharks are covered in toothlike scales called denticles

Colored micrograph of shark skin showing the complex three-dimensional structures of its denticles.

Gregory S. Paulson/Getty Images

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Cartilaginous fishes such as sharks, rays, skates and chimaeras grow three-dimensional scales on the surface of their skin. Each toothlike scale has a pulp cavity containing blood vessels and nerves and is covered in a mineralized, enamel-like tissue called enameloid. These scales—very unlike bony fishes’ flat dinner-plate-like scales—are called denticles and have widely different shapes and features, not just across species but also in an individual fish. Denticles found on a shark’s nose might be flat and round, resembling the patched surface of a soccer ball. But elsewhere on the body the denticles might look like overlapping cupped hands with ridges and points.

These denticles can serve a variety of functions, such as decreasing drag while swimming and perhaps even increasing thrust directly, explains Purdue University biomechanist Dylan Wainwright. “We think they’re also functioning in some way as protection for sharks,” Wainwright continues. “They may protect from both big things like bites from other sharks [and] from small things like ectoparasites.” (Some fish have been observed rubbing against sharks’ rough skin to scrape off their own parasitic riders.)

We still don’t know where teeth come from

Two competing theories about the evolutionary origins of teeth have been battling back and forth for decades, vacillating with the latest supporting discoveries in developmental biology or the fossil record. The “outside-in” hypothesis suggests that toothlike dermal scales with pulplike centers covered in hardened mineral—similar to denticles found today—gradually migrated across the body’s exterior surface over successive generations of fish before moving inward to take up residence in our ancestors’ jawbones. The “inside-out” hypothesis suggests that teeth originated internally before migrating forward in the oral cavity to become oral teeth.

An investigation of a fossilized sawtooth shark’s rostral denticles (the “teeth” on the fish’s sawlike bill) showed complex internal structures incredibly similar to those found in shark teeth. This discovery suggests that the developmental gap between dermal scales and teeth is smaller than originally thought, edging the outside-in hypothesis ahead of inside-out once more. Given the inherently spotty nature of the fossil record, however, it is entirely possible that we will never know exactly where our oral teeth come from.

Some fish species have not one, not two, but three varieties of teeth

Most fish have two sets of teeth—the oral teeth located near the front of their mouth for grabbing and chomping and the pharyngeal teeth located in their throat for the slicing and dicing. But some fish, comprising a group known as osteoglossomorphs, have also developed a third set of teeth—bony plates formed by the roof of their mouth and their tongue (“osteo” means “bony”; “glossi” means “tongue”) that help crush and grind their food. “It seems like fish just put teeth wherever they want,” says Kory Evans, a fish biologist at Rice University, “and fishes can continue making teeth throughout their entire life, which is really impressive.”

The most numerous vertebrate fossils on the planet are microfossil fish teeth

As fish routinely replace their teeth, the shed teeth will fall to the bottom of the water column and become enshrined in the sediment. Unlike more porous bones, these hardened teeth are less susceptible to erosion and degradation. Given that fish have existed for 530 million years or so, it should come as no surprise that sediment from around the globe is chock-full of fish tooth fossils. But good luck spotting them in the wild. “They’re smaller than the human hair, but these little, teeny, tiny fish teeth can tell mighty stories,” says Elizabeth Sibert, an oceanographer and paleobiologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Resembling microscopic ice cream cones, these micro teeth can vary in thickness, length, curvature, presence or absence of barbs, and so on. From the relative abundances of these teeth over time and the geographic distribution of differently shaped ones, Sibert and her collaborators can make inferences about animal diversity, animal abundance and food webs from oceans long past. And just how many of these microfossil teeth might be out there? “Certainly billions,” Sibert guesstimates, “and I think trillions might not be that far off.”

Parrotfish beaks, built from compressed teeth, have the stiffest biomineral ever found

Heavybeak parrotfish (Chlorurus gibbus) featuring an impressive beak.

Ute Niemann/Alamy Stock Photo

Most parrotfish species munch through coral in search of polyps and algae (contributing to white sandy beaches), but biting through coral is no easy feat. Parrotfish beaks are composed of the stiffest biological mineral ever discovered, supplanting limpet (snail) teeth, the previous record holder.

Parrotfish beaks form by compressing up to 1,000 teeth arranged in as many as 15 rows into one hard, conglomerate structure covered by a layer of enameloid. Crystals in the enameloid are woven together much like fabric but on the scale of two to five microns (smaller than a red blood cell). This woven structure affords one square inch of a parrotfish’s beak the ability to withstand a force equivalent to the weight of 88 elephants.

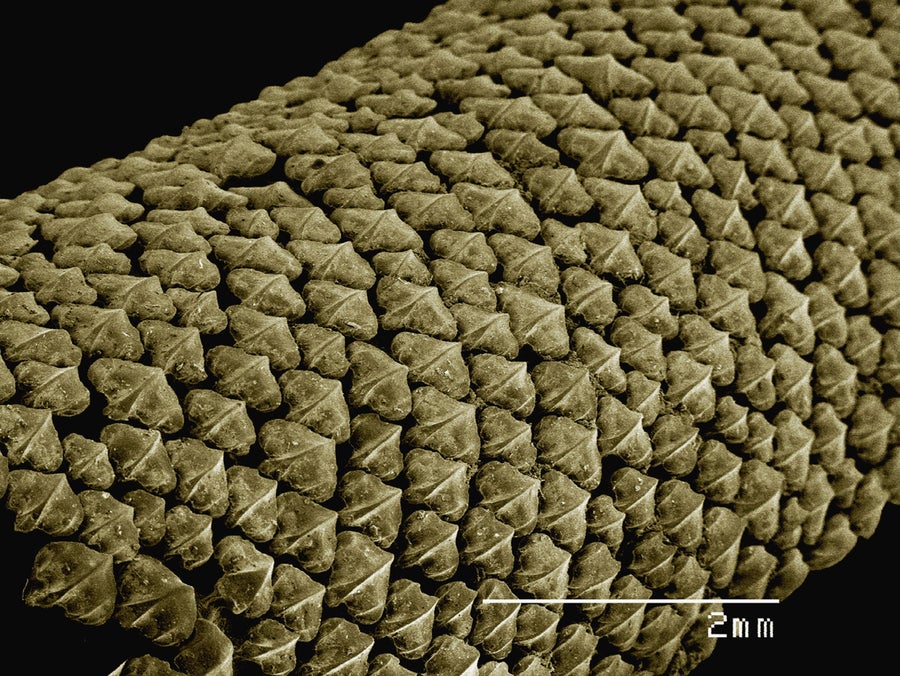

Deep-sea fishes’ transparent teeth may provide camouflage

Jagged, transparent fangs can be seen in the mouth of this deep sea Anglerfish (Melanocoetus sp.) female.

Nature Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

Deep-sea fish will never win beauty pageants, but surviving under hundreds of meters, if not several kilometers, of water is not easy—and these fishes are brimming with incredibly bizarre adaptations that should definitely win them some awards. The long, spindly, transparent teeth of anglerfish, dragonfish, and the like are fascinating in more ways than one. First, while the long fangs may look sharp, these teeth are actually not designed to puncture but to trap! Many deep-sea fish species have “depressible” teeth that bend only inward and function like a one-way valve. Food can come in, but it can’t go out. Additionally, research suggests that a dragonfish’s smile doesn’t exactly light up a room. Any ambient light (like that generated from luminescing prey) passes through the tooth structure instead of bouncing off a dense surface and reflecting outward, like it would from our own pearly whites. This lets the deep-sea nightmares sneak closer to prey without their exposed teeth giving away the game.

Snake fangs evolved multiple times yet still all look identical

While most reptiles lack fangs and venom, many different snake species have evolved mechanisms to deliver venom through their teeth. Snakes display two main types of venom-delivering fangs: grooved fangs, in which venom runs down a backside channel, and tubular fangs, in which venom flows through an enclosed delivery duct within the fang itself. Tubular fangs have evolved in three separate snake families (vipers, cobras and burrowing asps). In a class of animals where fangs are not all that common, how is it that fangs evolved not just once but multiple times across disparate snake families and converged on roughly the same structures each time?

The answer appears to have a root cause. Many reptilian teeth have a pattern of zigzagging indentations called plicidentine around their base, where they attach to the jaw. Scientists hypothesize that one of the zags eventually developed into a long channel running the length of the fang, which could then be fully encapsulated within the fang as a canal. The presence of plicidentine forms an evolutionary shortcut to venom delivery that made repeated evolution of that adaptation more likely.

Nature evolved metal teeth long before humans invented the saw

For a few lucky critters, “jaws of steel” is not too far off from the truth. Some animals have evolved chompers that contain iron to reinforce and protect their teeth from wear and tear. Beavers are a prime mammalian example; their incisor enamel is enriched with iron and capable of withstanding the repetitive gnawing and chomping of fibrous plant tissue. Researchers recently learned that Komodo dragon teeth also contain iron strategically located along their serrated edges. This is particularly surprising given that Komodo dragons, like most reptiles, replace their teeth frequently. The metabolic cost of investing in and growing thousands of iron-laden teeth over their lifetime must be worth it.

Narwhal tusks are overgrown canine teeth

Narwhal (Monodon monoceros) crossing tusks above the water’s surface off of Baffin Island, Nanavut, Canada.

Nature Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo

The defining characteristic of the narwhal, or “unicorn of the sea,” is a long, spiraling tusk erupting from the animal’s forehead. But it’s not a horn—it’s a tooth. Narwhals have two large teeth embedded horizontally in their skull, and one of them (usually the left tooth, though sometimes the right or rarely both) erupts from the skull to continue its growth into what we think of as a horn. And even more strangely, these tusks always spiral in the counterclockwise direction, even in the odd instances where a narwhal has two horns. This might be the mechanism by which the tusks of narwhals grow straight, compared with the curved tusks of elephants and boars and the impressively large, curving canines of walruses and hippos. Additionally, the tusks are not covered in enamel, as most teeth are, but in cementum, a more flexible mineral coating. Given that most narwhal tusks are grown by males, it is no surprise that they have been shown to play a role in sexual selection.

Plaque-causing bacteria and fungi can walk across the surface of our teeth

We have known for a while that bacteria residing on human teeth can cause surface damage leading to plaque buildup and tooth decay. But scientists made a few startling discoveries more recently that might provide the motivation to brush and floss just a bit more regularly. Not only did they discover fungi in the saliva samples of children with severe tooth decay, but they also saw the bacteria and fungi interacting under a microscope! These conglomerations are capable of spreading or “walking” across the surface of teeth and combining with other Frankensteinian bacteria-fungi colonies to grow larger and larger.