In the pantheon of dinosaur royalty, sauropods may have been the biggest and tyrannosaurs the deadliest. But the ceratopsians, ankylosaurs and stegosaurs were the most metal dinosaurs of all. With their horns and spikes, body plates and tail clubs, these horned and armored dinosaurs have long captured popular imagination. In the early 1900s American paleoartist Charles R. Knight depicted one of these weapon wielders, the plant-eating Triceratops, as a worthy adversary of carnivorous Tyrannosaurus rex; Stegosaurus makes regular (and formidable) appearances in the Jurassic Park movie franchise that began in 1993. Yet despite our enduring fascination with these “living tanks,” as armor-bearing dinosaurs have been described, many details of their anatomy—including the composition and even the functions of their impressive accoutrements—have remained unknown.

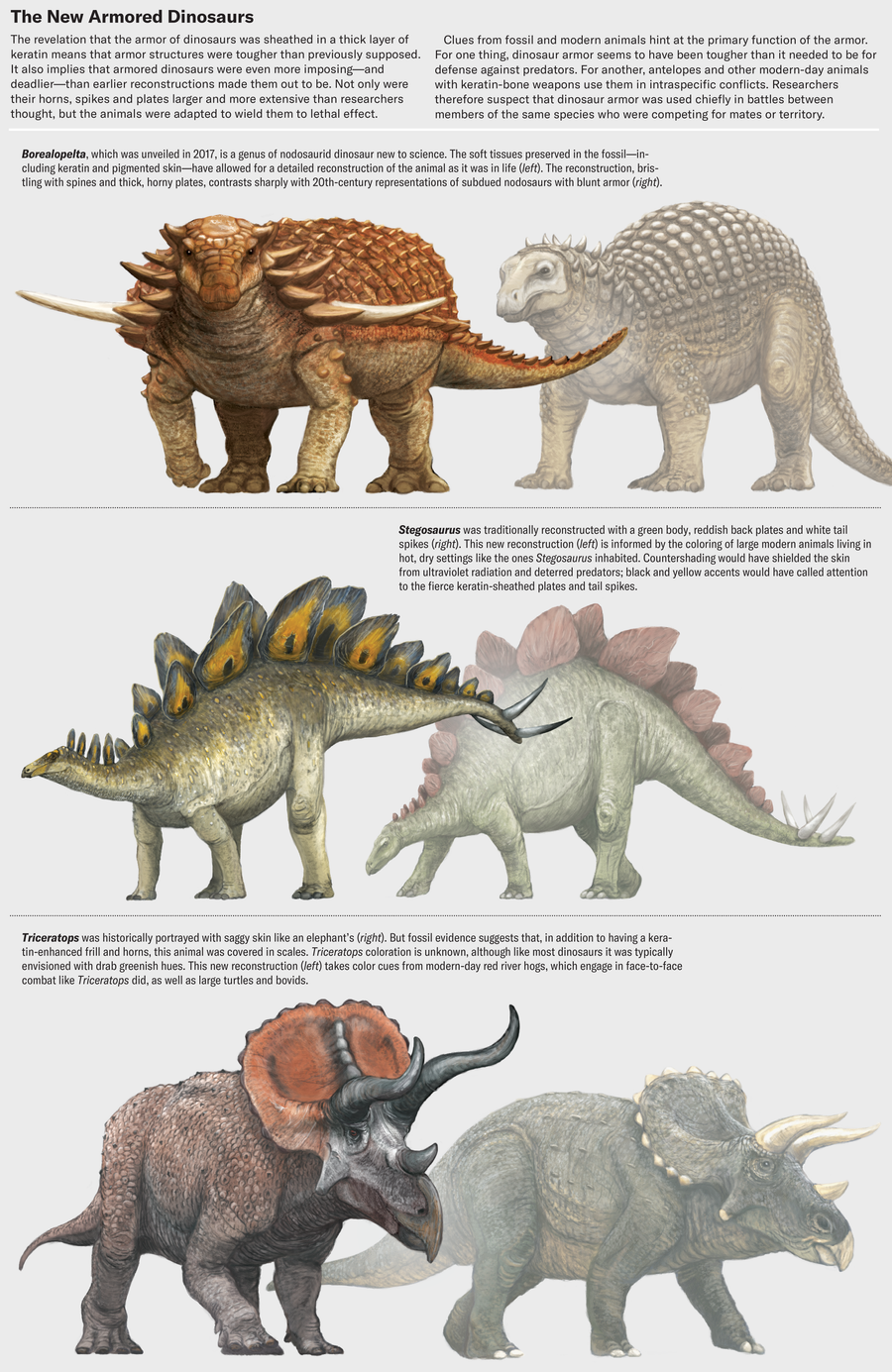

The problem stemmed from the scarcity of fossils of these animals that, even when found, often consisted of mere scraps. These recovered specimens also preserved only the hard bony parts, not any of the associated soft tissue. In their efforts to reconstruct armored dinosaurs as they were in life based on this meager evidence, paleontologists took what they thought was a conservative approach and assumed that the bony remnants of the armor of these long-dead dinosaurs constituted the bulk of the armor in life. Those reconstructions revealed some magnificent creatures—ceratopsians equipped with three-foot-wide frills, stegosaurs brandishing 30-inch-long tail spikes, nodosaurs bristling with shoulder spikes nearly a foot and a half in length.

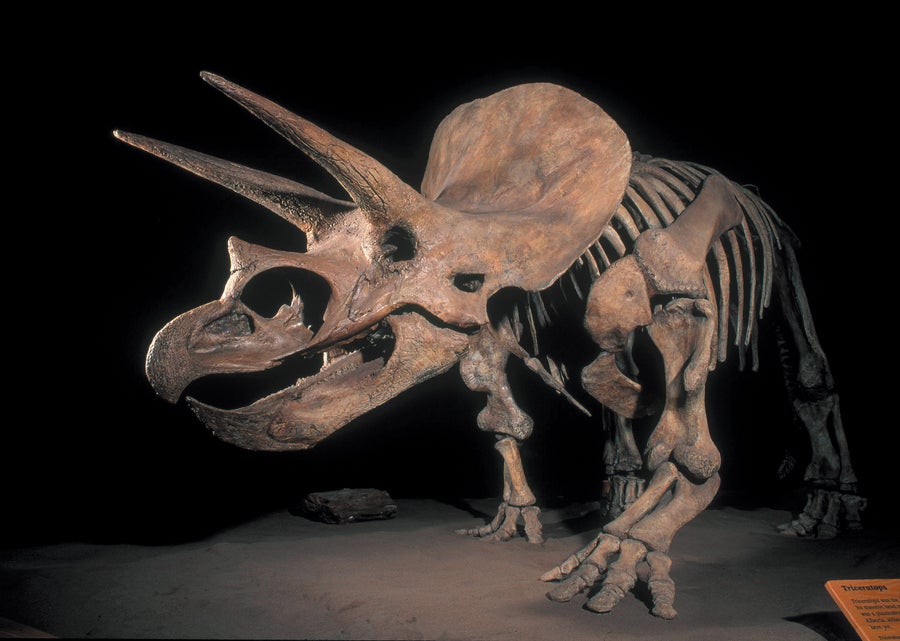

Triceratops, an iconic member of the ceratopsians, or horned dinosaurs, roamed western North America between 68 million and 66 million years ago.

Francois Gohier/Science Source

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But in recent years researchers have unveiled new fossils that preserve aspects of armored dinosaur anatomy never seen before. These incredible specimens reveal the true makeup of dinosaur armor and weaponry. With this new information in hand, my colleagues and I have performed new mechanical analyses of the horns, spikes and plates of heavily armed and armored dinosaurs. Our fresh look at these armaments shows that they were even more impressive than previously thought. The findings may settle a long-running debate over the primary function of these spectacular structures.

Our discoveries are based primarily on two extraordinary fossils first announced in 2017. One was an armored dinosaur with a massive tail club that Victoria Arbour, now at Canada’s Royal BC Museum, and David Evans of the Royal Ontario Museum named Zuul for its resemblance to the monster from the 1984 movie Ghostbusters. The second fossil came from a nodosaurid, a type of armored dinosaur known for its wicked shoulder spikes. Caleb Brown of the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta and his colleagues called this animal Borealopelta, meaning “shield of the North.”

The specimens of both Zuul and Borealopelta represented species new to science, but what makes these fossils truly thrilling is their exquisite condition. They are among the best-preserved dinosaur remains ever discovered, exhibiting not only the bony portions of the armor but also associated soft tissues. With these fossils, researchers could, for the first time, observe the material composition of the elaborate body coverings of armored dinosaurs.

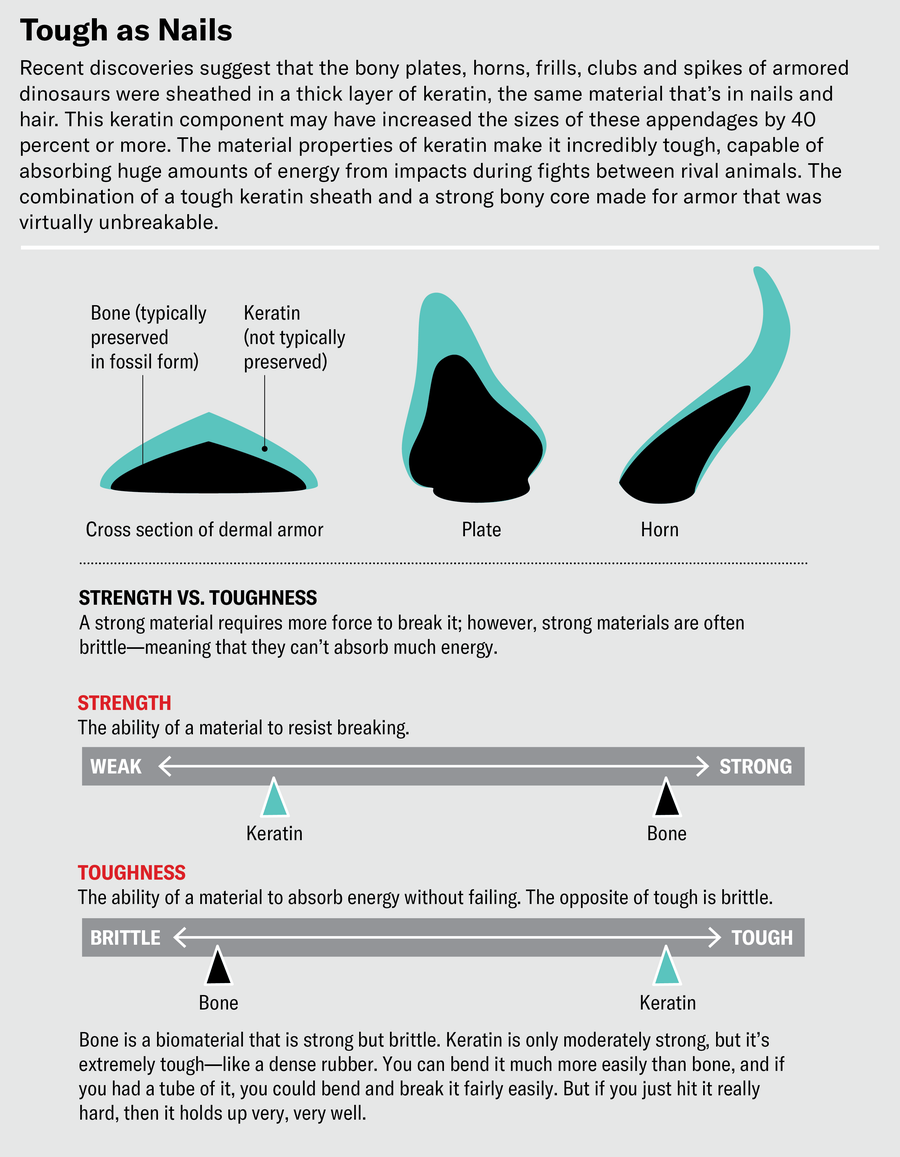

Before the discoveries of the Zuul and Borealopelta fossils, some scholars had deduced that the bony armor pieces (called osteoderms) on the likes of Ankylosaurus and Stegosaurus were just cores of bone that supported an outer covering made of keratin (the same material that hair, nails and horns are made of). The new specimens confirmed this speculation, demonstrating that the armor of these dinosaurs had an outer layer of keratin, which was supported by the bony osteoderms.

Moreover, this keratinous covering was far more substantial than previously constructed. The Borealopelta fossil, which preserves the most armor, shows that keratin sheaths increased the linear dimensions of the thickest parts of the armor by 30 to 40 percent. But because the keratin in this specimen is partially worn away, we know that it was even thicker in life. Having examined this fossil myself, I suspect that the increase could have been significantly larger than 40 percent.

This insight into the structure of the armor revolutionized our understanding of these dinosaurs. First, it meant that the armor’s performance was far different (and more impressive) than previously recognized. Second, because most dinosaur armor shows telltale signs of connections to a keratin sheath, the keratin-to-bone ratios of the Borealopelta and Zuul armor probably extend to other dinosaurs with bone-cored armaments. That is, the spikes, plates and horns of all dinosaurs with armor—from horned ceratopsians to plated stegosaurs—were probably more than 40 percent larger in life than what we see in their skeletons.

To understand the extraordinary implications of having armor made largely of keratin, we must look at the material properties of keratin. Key to this discussion are a material’s strength and its toughness. Strength is the resistance of a material to being broken by being deformed. If you have a rod of a given material and it’s difficult to snap that rod in half, then the material is strong. Toughness, in contrast, is the measure of a material’s ability to absorb energy. If you can hit a chunk of a material very hard and it survives, then it’s tough; if it breaks when struck, then it’s brittle. There are often trade-offs between these two properties. Materials that are very strong are often comparatively brittle. Take glass, for example: it’s quite strong, but even a light impact can cause it to shatter. The fragility of glass is a result of low toughness, not low strength.

When viewed this way, keratin is a special biological material. Unlike bone, which is very strong but brittle, keratin is only moderately strong but extremely tough. It makes for ultraresilient weaponry and armor.

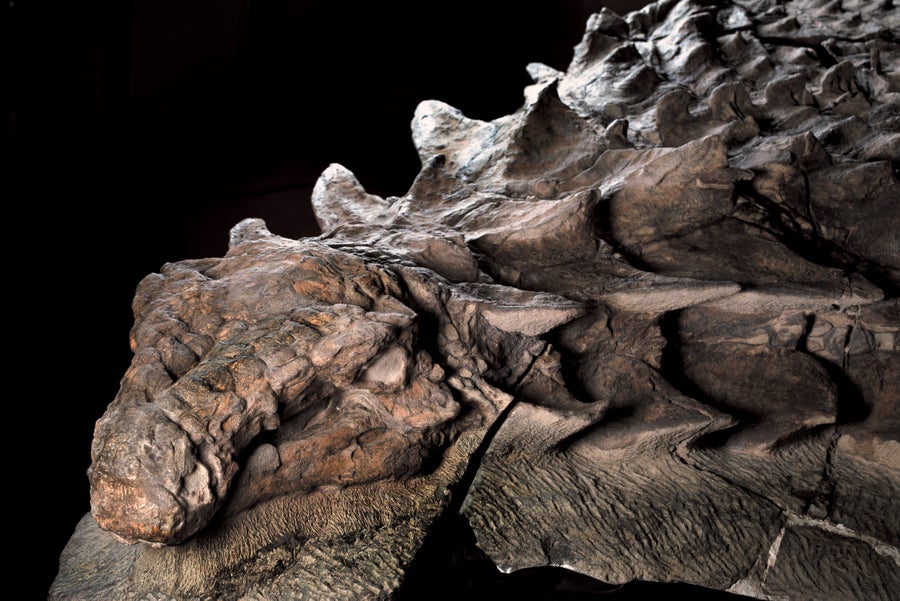

This 110-million-year-old fossil of Borealopelta, a nodosaurid ankylosaur from Alberta, Canada, is one of the best-preserved dinosaur fossils ever found.

Consider the keratin quills of African porcupines, which can mortally wound lions foolish enough to attack the heavily armored rodents. Bone can break when subjected to the high bite forces of lions. But the keratin quills soak up the energy from the bite and retain enough of their shape to function as lethal spears that the porcupine can drive deep into its attacker’s face and jaws.

Even more relevant to the discussion about armored dinosaurs are the horns of living antelopes, sheep and goats. Bighorn sheep ram one another with hefty cranial appendages made not solely of bone but of thick keratin built around a bony core. The overall physical properties of the horns in these great mammalian jousters arise from the pairing of the tough outer keratin and the stronger, but more brittle, bony core. This combination marries the best of both worlds: the tough keratin sheath can absorb a lot of energy, and the strong, stiff core resists bending and breaking.

The structure of the horns of living antelope also means the contact surface is inert. Damage to keratin does not cause pain or bleeding. In contrast, bone is a living tissue with substantial blood supply and nerve endings. Having exposed bone as armor is dicey—damage to it can lead to hemorrhaging or debilitating pain.

The data from Zuul and Borealopelta, along with comparisons to modern animals, tell us that the armor of dinosaurs was not a stiff, brittle bone armor. It was an exceptionally tough bone-keratin composite. The thick outer keratin did the heavy lifting—as the surface of the armor, it was taking the hits. Any damage to the keratin when the animals came to blows would have been trivial, with no bloodshed or pain. The core, made of bone wrapped in skin tissues, provided strength and produced the keratin, sensing hits and replacing losses. The net effect was a rugged, self-repairing armor capable of absorbing immense amounts of energy.

Not only are the bony plates, or osteoderms, that covered the body present in this specimen (top), but so, too, is the keratin that covered the bony plates (bottom).

Brown (whose team described Borealopelta) and I are actively studying the energy-absorption capacity of this armor. In the fall of 2024 I announced the first estimates from our work at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. These preliminary estimates suggest that the thickest parts of the armor on Borealopelta might have been able to absorb an energy volume roughly similar to that of a high-speed automobile collision. At minimum, the bone-keratin composite structure of this animal’s armor would have increased its toughness by 20 times that of armor made purely of bone. Such tough armor would be quite valuable in a world of predators that, experts agree, had very high bite forces. Armor made mostly of bone, with just a thin covering, would have almost certainly cracked or shattered under attacks from these predators. In this regard, it was clearly an advantage to have the outer, “business end” of the armor composed of keratin.

That said, the armor of Borealopelta seems to have been overbuilt for withstanding the bite of a large, predatory dinosaur. And a predator would have struggled to directly bite Borealopelta’s low, wide body. I wondered if there were any situation in which a predator could deliver a full-force bite to one of these living tanks and do any real damage to the armor.

The keratin-bone composite of the armor made it at least 20 times tougher than armor made solely of bone and may have been able to withstand impacts as forceful as that of a high-speed car crash. The fossil also includes a pebbled mass that appears to be the remnant of the animal’s last meal.

In 2019 I teamed up with physicist Seamus Blackley and his team of engineers in southern California to find out. We designed and built a mechanical test of Borealopelta’s armor for a Canadian Broadcast Channel program. In it, we pitted a synthetic version of the armor against a model of the largest predator Borealopelta could encounter, the theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus. In developing the bite rig for this model, we made sure it accurately represented the head size and shape, bite force, and tooth properties of the predator. We then tested a worst-case scenario in which the predator somehow managed to slice into Borealopelta’s armor at a steep angle. Even with those odds stacked up against the armor, and despite the fact that we were using just a small, bite-size chunk of it, the enormous and frankly terrifying bite rig had to hit the armor in exactly the same place twice before doing real damage to it.

We never built the grandest, most heavily armored parts of Borealopelta. Instead we modeled the less intimidating armor that covered the back half of its body. One can confidently assume that any attempt by a predator to have a go at the front of Borealopelta would have been futile—and probably an excellent way to get killed. Whereas the back end of the animal was covered in an impressive series of small keratin-covered osteoderms that formed an interlocking mosaic, the front end of Borealopelta (and other nodosaurs) was straight-up outrageous. Bladed plates covered the beast’s neck, and massive spikes protruded from its shoulders. It looked like a war machine from the video game World of Warcraft.

Zuul, another beautifully preserved armored dinosaur, lived in Montana 76 million years ago. The fossil includes a complete skull and a tail club. Analysis of injuries to the animal’s flanks suggests that they were inflicted by the tail club of another Zuul.

During the analysis for the CBC test, I came to refer affectionately to the massively fortified area of Borealopelta running from its neck to its shoulders as the “kill box.” Anything that found itself in that location while up against an angry Borealopelta was not long for this world. That is … unless the animal squared up in that danger zone was another Borealopelta.

Paleontologists have long debated the function of dinosaur armor: Did it serve as protection against predators, weaponry for combat with members of their own kind, sexual display, or some combination of these roles? These new discoveries may tip the scales. If the armor of Borealopelta was tougher than it needed to be for predator defense, then perhaps protection against meat-eating dinosaurs looking for a meal was a secondary function of this feature. In that case, what might the armor’s primary function have been? We can look to those living animals with elaborate bone-keratin weaponry for insights.

With permission of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. © ROM

In the modern world, such structures can be used to fight off a predator, but their primary functions are nearly always related to display and fighting within the same species. In biology, we call such an encounter intraspecific combat, and it can be absolutely brutal. Bighorn sheep ram one another with roughly 60 times the force needed to shatter a human skull. And they do it over and over again, sometimes for hours. Deer have been filmed with the head of a rival impaled on their antlers. Incidentally, deer get away with using pure bone weapons without a keratin component because the bone of mature antlers is dead and so doesn’t bleed if damaged, and deer shed their antlers annually.

Contrary to the Hollywood narrative of predators facing herbivores in a duel to the death, actual hunting is about catching a meal, not a prize. To that end, most predators target juveniles. A carnivore needs to eat; it doesn’t need to prove itself. The most epic battles in the animal world are not between predator and prey; they’re between the armed and armored herbivores, who fight for status and mates.

Perhaps the same was true in the Mesozoic. In a study of Zuul published in 2022, Arbour and her colleagues showed that the animal had sustained, and healed, injuries to its flanks that were most consistent with being hit by the tail club of another Zuul. Furthermore, baby nodosaur specimens show that the kill box of these animals didn’t fully develop until later in life—even though predation risk would have been higher when they were small. These findings, combined with the overbuilt nature of Borealopelta, suggest that at minimum the most extreme weapons of armored dinosaurs were mostly used in combat between rivals of the same species. Because this pattern also matches what we see in the world today, the best available explanation for dinosaur armor is that it was an adaptation to battles within the same species. That it could also dispatch a would-be predator in grisly fashion when needed was a bonus.

Thanks to the two outstanding armored dinosaur specimens Zuul and Borealopelta, we now know what to look for to identify thick keratin armor in fossil animals—and we see the telltale signs everywhere. From fibrous, blood vessel–filled bone edges in the plates of Stegosaurus to grooves along the horns of Triceratops, evidence for robust keratin sheaths is commonplace; it’s been hiding in plain sight all along.

Stegosaurus, known for its vertical back plates and spikey tail, lived in the western U.S. and Portugal during the Late Jurassic period, between 159 million and 144 million years ago.

Jon G. Fuller/VWPics/Redux

Keratin not only would have changed how the armor structures performed—increasing their toughness while decreasing their strength—it also would have fundamentally changed how these animals looked. This insight has led to the latest in a long series of visual updates to dinosaurs that have come from a rethinking of their anatomy that began in the late 1970s. Over the past decade quantitative assessments of posture, gait and skeletal mechanics have become well established in paleontology. As a result of these analyses, hunched ceratopsians and slump-tailed Stegosaurus from a century ago have given way to more erect, muscular builds with heads held high. Ankylosaurs are now envisioned as low, extrawide battering rams rather than vaguely melon-shaped animals.

The corrected postures and anatomies yield reconstructions that are simultaneously more dazzling and more lethal than the ones scientists generated before. These animals weren’t just armed to the hilt, they were also adapted to wield their weapons to the deadliest effect. Far from being the passive animals imagined in centuries past, armored dinosaurs were among the most dangerous creatures in their ecosystems, magnificent to behold but terrifying to face in combat. Few animals would have dared challenge such imposing beasts apart from their equally well-equipped rivals. They were the gladiators of their time, ready to do battle at a moment’s notice in their quest for status, mates and territory.